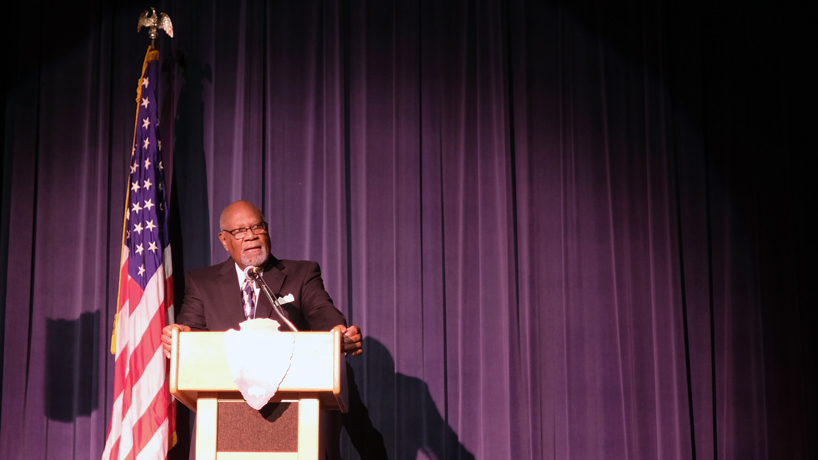

Robert Stanton delivers a passionate speech about the founding principles of the National Park Service at the Gateway Arch National Park Visitor Center auditorium Thursday evening. Stanton served as the 15th director of the NPS, and last year, he accepted a position as scholar in residence in the College of Education at UMSL. (Photo by Burk Krohe)

As Robert Stanton stood on the stage of the Gateway Arch National Park Visitor Center auditorium Thursday evening, he reminded the audience of the National Park Service’s original mission established in the National Park Service Organic Act of 1916.

Stanton, a former director of the NPS and scholar in residence in the College of Education at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, spoke poetically, yet forcefully, on the subject to a rapt audience of about 100 members of the UMSL and greater St. Louis communities.

He noted that the Organic Act established the NPS as a bureau of the United States Department of the Interior, but more importantly, set forth its responsibility to preserve, promote and regulate the nation’s precious natural resources for the benefit of all Americans.

“The mandate, the recurring responsibility of your National Park Service, is to maximize any resources that might be available,” Stanton said. “It has a responsibility by law to try to connect every American citizen with their heritage – both natural and cultural – that is preserved in the National Parks. Think about it my friends – an awesome responsibility.”

Over the course of an hour, Stanton discussed the bureau’s pursuit of that mission and the strides, and missteps, it has made while also peppering in several history lessons. The talk was part of a special event, “Reshaping the National Park Service for ALL: An Evening with the Honorable Robert G. Stanton,” sponsored by UMSL, the National Park Service and the Jefferson National Parks Association. The event also included brief remarks by UMSL Chancellor Kristin Sobolik, President and CEO of the Jefferson National Parks Association Davide Grove, NPS Regional Director Herbert C. Frost and NPS Regional Relevancy, Diversity and Inclusion Program Manager Nichole McHenry.

Stanton began his career with the NPS in 1962 as a seasonal park ranger at Grand Teton National Park, becoming one of the first Black rangers to work at the park. He had been recruited to serve in the position under the auspices of then-Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, who was making a concerted effort to diversify the NPS workforce.

That summer led to Stanton’s storied career serving the NPS as a ranger, superintendent, deputy regional director, assistant director, associate director, and regional director of the National Capital Region. In 1997, it culminated with President Clinton naming him the 15th director of the NPS. The historic nomination made him the first Black director in the bureau’s history and the first director to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate.

E. Desmond Lee Endowed Professor of Experiential and Family Education Theresa Coble was drawn to Stanton’s story as well as his expertise in historic preservation and natural resources and tapped him to serve as a scholar in residence for her Heritage Leadership for Sustainability, Social Justice and Participatory Culture doctoral cohort at UMSL.

“This unique program allows doctoral students to examine the link between natural and cultural heritage while also grappling with the difficult topics surrounding heritage sites such as bias, ethics, oppression, privilege and trauma, and they do so under the guidance of National Park Service experts,” Sobolik said. “One of these experts is Bob Stanton who joined our campus as a scholar in residence in the College of Education this last year. Bob has brought depth, nuance, wisdom and experience to our EdD students, and he’s helped them develop new skills and perspectives they couldn’t get in any other way.”

Stanton touched on several of those difficult topics Thursday.

During his career, Stanton worked diligently to increase the diversity of the bureau’s staff and public programs to better serve minority populations in an effort live up to the bureau’s founding principles. It’s an issue the doctoral cohort often examines and one Stanton invited the audience to consider.

“The continuing debate is, do the areas represented in the park system really reflect the richness of our diversity, the richness of our heritage?” Stanton said. “If you were to take a look at the 424 areas that have come into the National Park System in the past 20 to 30 years, you would see that many areas now represent in a fuller sense, the breadth of what I refer frequently to as the ‘face of America.’”

However, this was not always the case.

Stanton called attention to Scott v. Emerson, a court case decided mere blocks from Gateway Arch at the Old Courthouse that would eventually go all the way to the Supreme Court as Dred Scott v. Sanford. The court’s decision in that case held that the U.S. Constitution did not extend citizenship to people of African descent, and therefore, they were not entitled to rights and privileges conferred by the Constitution.

He also pointed to Plessy v. Ferguson, the landmark Supreme Court case that became the basis for the “insidious” doctrine of “separate but equal.” It was a doctrine Stanton experienced as a young man, and one that demonstrably affected National Parks.

“It was a doctrine of which I lived under for 24 years – absolutely nothing equal under that doctrine,” Stanton said. “But how would it play out in the National Parks? Well, since it was constitutional that you can exercise discrimination or segregation, what happened in many instances is that the parks in those states and jurisdictions that actively supported and practiced segregation sort of fell in line.”

Stanton encouraged the audience to not shy away from such harsh realities in American history. Instead, he advocated viewing them as opportunities to learn and make greater strides toward equality.

“We have truly erred,” he said. “We have made grievous mistakes, but we are mature and imaginative as a people and as a nation. If you are mature, you can be open and honest that you have made a mistake. But that’s only one half of it. The other is that you have a resolve, not to repeat, but rather to grow from that mistake.”

National Parks, and the history and heritage they contain, can play an instrumental role in that growth. Furthermore, partnerships with institutions such as UMSL can bolster that potential.

“The Park Service is a laboratory and a library of how we have made our decisions and what steps we need to continue to advance,” Stanton said. “The lessons have been taught as to what the consequences are when we make a mistake. The real responsibility is, are we willing to learn?

“Learning is difficult. You have to put away old thoughts and old ways of doing things. But the University of Missouri–St. Louis is providing the resources and support for all of us to learn, and the National Park Service will stand with you in that endeavor.”

Stanton closed his speech with a quote from civil rights activist and humanitarian Mary McLeod Bethune and a call for a brighter future.

“I leave you a responsibility to our youth,” he said, quoting Bethune. “The world around us really belongs to youth. For youth will take over its future management. Our youth must never lose their zeal for building a better world. They must not be discouraged from aspiring towards greatness. For they are to be the leaders of tomorrow.”