Laura Miller, the Eiichi Shibusawa-Seigo Arai Endowed Professor of Japanese Studies and professor of anthropology, detailed the history and modern fandom of kofun during “Kofun Mania,” a special digital event sponsored by UMSL Global and the Japan America Society of Chicago. (Screenshots by Burk Krohe)

Laura Miller first became captivated by kofun – Japan’s ancient, megalithic burial mounds – while researching a book on another subject, “Diva Nation: Female Icons from Japanese Cultural History.”

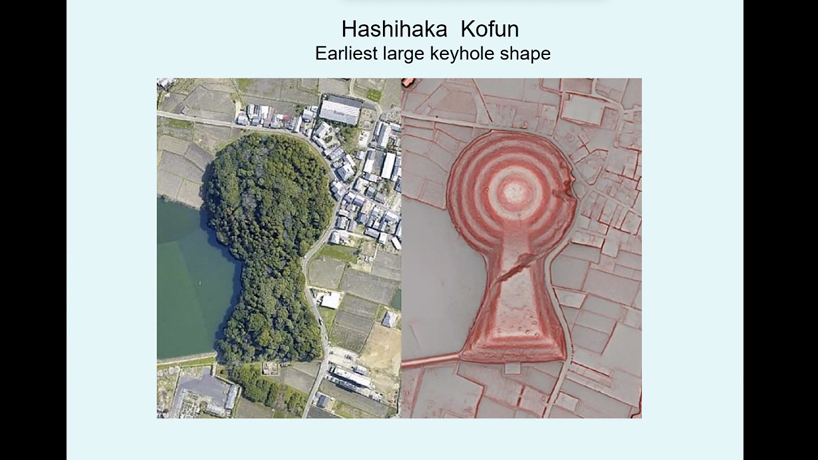

She was investigating Himiko, the queen of Yamatai in ancient Japan, and over the course of her research, she visited the Hashihaka Kofun in Sakurai, the rumored tomb of Himiko, numerous times. Those visits would spark a passion for kofun – a fascination she shares with people across the globe.

More than 30 of those kofun fans tuned into a special digital presentation, “Kofun Mania,” Thursday evening to hear Miller, the Eiichi Shibusawa-Seigo Arai Endowed Professor of Japanese Studies and professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, detail the history and modern fandom of kofun. A short Q&A session also followed Miller’s talk. UMSL Global and the Japan America Society of Chicago sponsored the event.

Miller began her 30-minute presentation with an overview of kofun and their historical origins. She noted that they were constructed from the third to the seventh century, and initially, they were incredibly large earthen mounds.

“The earliest one was built in 248, and you have these huge bursts of kofun constructed until about 538,” Miller explained. “Then they were replaced by this other type of kofun, which was either stone or some sort of quarry or chamber-style kofun and these were much smaller. Those type of kofun lasted for another 100 years, and then they died out.”

Kofun were built in many shapes including circles, squares and hexagons. However, the zempō-kōen-fun, or keyhole shape, is the iconic form. The remains of a person buried in a kofun would be put in either a stone or ceramic coffin and placed in a round part of the structure.

“Together with the remains, there would be some grave goods put in the coffin with a deceased person,” Miller said. “It could be in the coffin or around the coffin and that would be things like Chinese bronze mirrors, bronze weapons – especially swords and daggers – vessels and so on. Then on the perimeter outside of the kofun, so not buried but put outside the kofun, you would have these ceramic cylinders or sometimes cylinders with images of people or animals.”

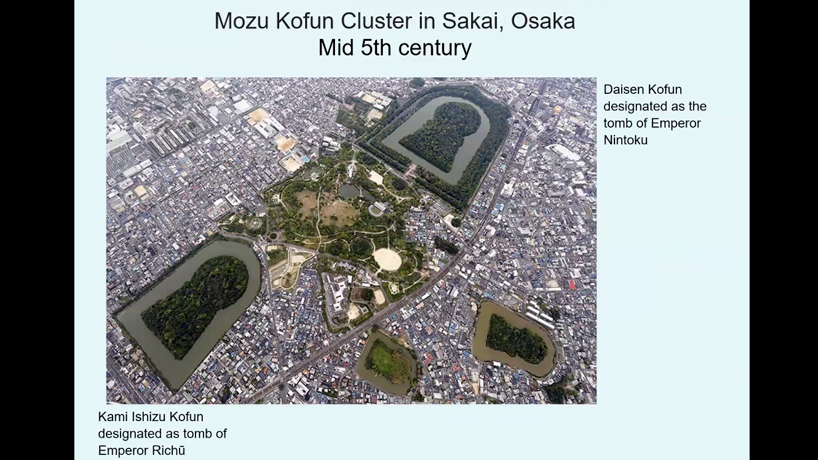

Of the more than 160,000 kofun in Japan, the majority are located in the Kansai region of the country, particularly in the Nara and Osaka Prefectures.

The city of Sakai worked for more than a decade to have Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The earliest of the large keyhole-shaped kofuns is the Hashihaka Kofun – the one that first grabbed Miller’s attention. But Miller pointed out that most kofun fans are interested in a collection of fifth-century tombs now called the Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group.

“That Mozu Group is found in the city of Sakai in Osaka, and they’ve just been relentless over more than a decade trying to obtain UNESCO World Heritage Site status,” she said. “They were really active in promoting the kofun group, lobbying for it, and they finally received the World Heritage status in 2019.”

From there, Miller transitioned to the next portion of the talk, a discussion about kofun cultural expressions. She said that cities such as Sakai have done well highlighting local kofuns and attracting tourists through kofun matsuri, or traditional festivals. They are often advertised as events where visitors can “feel the romance of the past.”

“So, these towns want to have kofun matsuri because it attracts tourism and helps the economy, but it also lets them show pride in their local history,” Miller said.

The festivals offer a variety of activities from traditional taiko drumming to magatama bead making to storytelling. Visitors can also partake in food stalls, serving dishes such as takoyaki. Many people also cosplay in kofun-period clothing.

Cultural expressions of kofun also extend to a number of consumer goods, as well as advertising. In Japan, it’s common to find kofun-shaped products such as bento boxes, jewelry, pillows and sketchbooks. Keyhole kofun motifs are also found in beer and wine labels and coffee packaging.

Miller concluded the presentation with an examination of why kofun have become an object of interest for people.

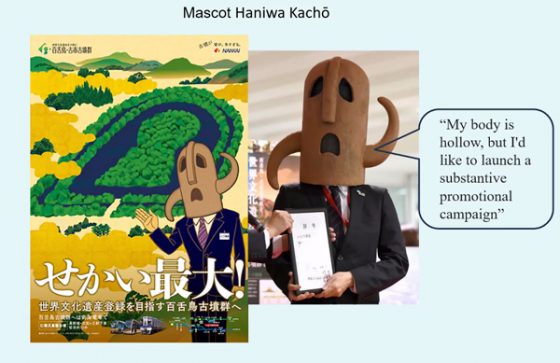

“I think there’s a few things going on, a few reasons,” Miller said. “The two I think that are obvious have to do with something we’ve already looked at, which is the regional and civic efforts that groups have made to bring attention to their kofun. For example, the city of Sakai in their effort to get the World Heritage Site designation spent many years hiring designers to make cute cartoon goods, and they also created this mascot – Haniwa Kachō.”

She posits that using cute mascots such as Haniwa Kachō on goods and posters put a spotlight on kofun at a time when few people were paying attention. The second major influence on “kofun mania” has been Marikofun. The Osaka-based singer and writer has traveled to more than 1,000 kofun sites throughout Japan and produced books and YouTube videos about the subject.

“She’s just so enthusiastic and is very infectious,” Miller said. “She’s from Osaka, and she speaks in a very strong Osaka dialect. So, I think she’s making kofun appealing to people who are not scholars or academics.”