(From left) UMSL History Professor Andrew Hurley, AECOM Principal Steven Duong and Living Earth Collaborative Postdoctoral Fellow Kaylee Arnold respond to questions from the audience while seated on stage at the Anheuser-Busch Theater at the Saint Louis Zoo during the Whitney and Anna Harris Conservation Forum. (Photo by Derik Holtmann)

Warmer days are becoming the norm around the globe amid changing climate, and the sweltering conditions are often felt most acutely in cities.

St. Louis is no exception. Dense concentrations of buildings – many of them made of brick – surrounded by paved surfaces absorb and retain heat. That contributes to rising energy costs for air conditioning and also increased levels of air pollution – which only further exacerbate the problem.

The Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center at the University of Missouri–St. Louis used its annual Whitney and Anna Harris Conservation Forum last Tuesday night to explore the issue of urban heat islands, their impact and what can be done to mitigate them in an event titled, “It’s Getting Hot in Here: Urban Heat Effects and St. Louis.”

An audience of nearly 100 people attended the free event in the Anheuser-Busch Theater in The Living World at the Saint Louis Zoo.

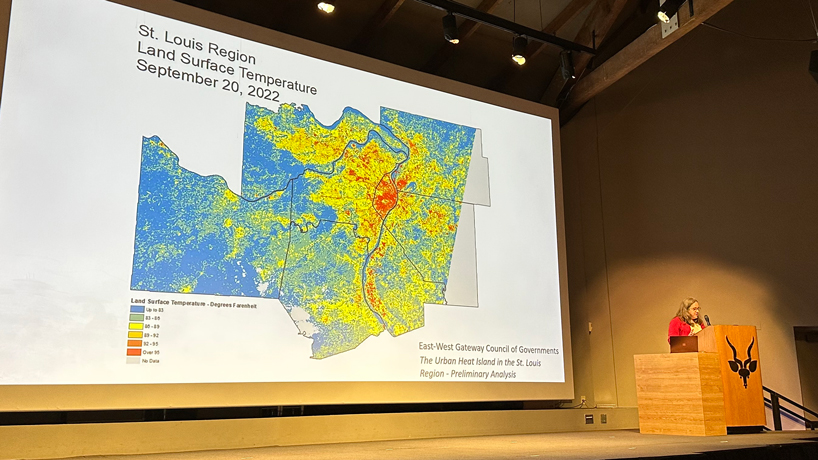

Aimee Dunlap, the interim co-director of the Whitney R. Harris Center, introduces the concept of heat islands by showing a map of land surface temperatures across the St. Louis region from the East-West Gateway Council of Governments. (Photo by Steve Walentik)

Aimee Dunlap, an associate professor in UMSL’s Department of Biology and the interim co-director of the Harris Center, set the stage for the discussion, sharing a map for the East-West Gateway Council of Governments showing the land surface temperature in the St. Louis region on September 20, 2022. It featured a high concentration of red – meaning the warmest temperatures – inside the boundaries of the City of St. Louis.

“Those red areas also overlap substantially with areas of impervious surface, roads, pavement, parking lots and buildings,” Dunlap said. “St. Louis is one of the oldest cities in the country in terms of the age of the housing stock. Most of our buildings predate 1950. Our beautiful brick buildings are plentiful but also hold on to heat. When you add that to the sheer amount of pavement in proportion to greener spaces, it and other factors place St. Louis in the top 25 cities in the nation for urban heat effects.”

For the rest of the evening, Dunlap turned the stage over to Andrew Hurley, a professor in UMSL’s Department of History; Kaylee Arnold, a postdoctoral research associate in the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University in St. Louis; and Steven Duong, a certified urban planner and principal with engineering consulting firm AECOM, who oversees urbanism and planning practice for the firm’s west region.

Hurley provided some historical perspective to the warming temperatures and expanding heat island found in St. Louis, including showing old newspaper ads from a time before air conditioning was common in St. Louis homes and theaters used the promise of “chilled air” to attract customers. He also showed photos of how, more than 70 years ago, St. Louisans dealt with heat, whether sleeping outside in public parks or visiting one of the main large public pools. But concerns about urban crime long ago kept people from parks overnight, and many of the old public pools were closed as a response to integration in the 1940s and 1950s.

Andrew Hurley, a professor of history at UMSL, responds to a question from an audience member during the Whitney and Anna Harris Conservation Forum. (Photo by Derik Holtmann)

“The prevalence of air conditioning has served to reduce the number of deaths from severe heat, but it remains a disproportionate threat to disadvantaged communities,” Hurley said. “As you can see, 19% of older adult homeowners reported at least one six-hour failure of central air in the previous year, and among African Americans, that figure was 25%. In the same survey, 28% of respondents experienced some discomfort even when the air conditioning was functioning, meaning that it wasn’t functioning very well in most cases. So the way that translates into health impacts is the way we see the distribution of deaths skew in recent extreme heat episodes.

“So there are a lot less deaths since the advent of air conditioning, but they’re concentrated in poor areas, and in St. Louis, predominantly African American neighborhoods.”

Arnold, a disease ecologist, discussed the relationships between parasites and hosts within an ecosystem and how rising temperatures have the potential to disrupt those interactions. The consequences of those disruptions aren’t always clear in what are often fragile balances.

“You may have more hosts in the system, but you also may have fewer hosts,” Arnold said. “If we’re having changes in what hosts are available in the system, that may have an impact on which parasites are able to infect them. That can also change the diversity of the parasites as well. And lastly, when we have changes to the parasite community or changes to the host community, that can have impacts on overall environment, particularly thinking about biodiversity. If the host community structure is altered, because of increased mortality, that can have an impact on the environment and the different organisms that are using the environment.”

Duong, meanwhile, described his work in urban planning and the pushback that often follows efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change in public policy.

Specifically, he talked about what has happened in the city of Phoenix, which continues to grow significantly despite rising temperatures and diminishing water. The city’s economic development success can make it harder to win support for climate action, but Duong suggested it is useful to reframe the economic incentives at stake.

“This is a classic issue in climate action planning – it seems unsurmountable, and the costs are outrageous,” he said. “But when you flip it into what we often call a cost of inaction study, suddenly you’re like, ‘Wait, wait, wait, yeah, it’s expensive, but the other outcome is existential doom for humanity.’ One is clearly more affordable than the other. That’s kind of the framework with which we approach this process.”