Missouri Institute or Mental Health Director Robert Paul (at left) leads the Precision Health Research team, including Jacob Bolzenius, Candice Adair, Natalie George, Julie Mannarino and Anshu Chappidi. (Photo by Derik Holtmann)

For many Americans, COVID-19 no longer occupies space at the forefront of their minds.

More than four years removed from the start of the global pandemic, life has more or less returned to normal. No more facemasks, vaccine cards or reminders to maintain social distancing.

But the SARS-CoV-2 virus hasn’t gone away. It remains, although it no longer feels so “novel” and is less virulent than it once was. It’s still infecting people, and in an estimated 30% of cases, still leading to symptoms such as fatigue, loss of smell, brain fogginess or post-exertional malaise that can persist for weeks, months or even years as part of a chronic condition known as “Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (“PASC”), also referred to as “long COVID.”

“Right now, clinicians don’t have a tool – a clinical aid – to help identify whether or not patients are at risk for having long-term problems,” said Robert Paul, the director of the Missouri Institute of Mental Health at the University of Missouri–St. Louis and a Curators’ Distinguished Professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences. “In most cases, they might not feel well for a few weeks but they are going to be fine, but others end up in the hospital with persistent symptoms or they might die. Those are such different outcomes, and clinicians don’t have a great way to identify, with good precision, what someone’s risk for those different outcomes are based on their initial symptoms.”

Relatedly, the biological mechanisms that cause the symptoms to persist after the initial period of infection remain unknown, which Paul said creates a major obstacle to research aimed at producing effective clinical therapies to prevent, treat or cure individuals.

Paul is hoping a pair of research projects funded by the National Institutes of Health that are currently being undertaken by MIMH’s Precision Health Research team – alongside experts in neurology at Yale University School of Medicine and infectious disease at the U.S. Military HIV Research Program and Chulalongkorn Medical School in Bangkok, Thailand – might help increase understanding of how the virus works in the human brain. That, in turn, could improve clinicians’ ability to recognize the patients most vulnerable to longer-term complications from the virus so that they can get the most effective treatment.

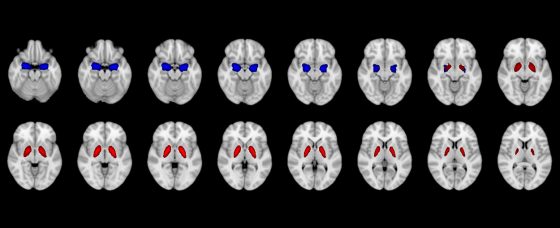

Research conducted by the MIMH Precision Health Research team implicated smaller volumes of the amygdala (blue) and pallidum (red) in differentiating individuals who acquired COVID compared to individuals who did not within 2 years. (Image courtesy of the MIMH Precision Health Research team)

Paul and his team have been collaborating with Dr. Serena Spudich, co-director of the Yale University School of Medicine’s Center for Brain & Mind Health and the division chief for neurological infections and global neurology, on a $3.2 million grant from the National Institute of Mental Health titled “Longitudinal determination of nervous system consequences of SARS-CoV-2 in virologically suppressed people with HIV-1 treated in early infection.” Nearly $700,000 of that funding has been directed to UMSL, with Paul serving as the co-principal investigator.

The study is focused on adults who have undergone extensive clinical profiling for up to 15 years as part of the largest ongoing investigation of the earliest biological dynamics of HIV and long-term responses to HIV treatment.

“Because we have all that information before people became infected with COVID, and since we follow them long-term, we have the pre-COVID and post-COVID evaluations of these individuals,” Paul said. “We have just a remarkably deep level of understanding of their immune systems and biology, but also their mental health and their brain function.”

Published work from the cohort in Bangkok has revealed that HIV can be detected in the central nervous system within eight days from the date of initial infection, but HIV treatment does not eradicate the virus from the body, leaving viral reservoirs that continue to disrupt the immune system despite successful control over viral replication outside of the brain. Paul and his collaborators are interested in trying to learn whether COVID-19 also establishes early viral reservoirs in the brain or synergizes with HIV-related viral or immune mechanisms to increase the risk of long COVID-19, but now that remains unknown.

Paul and his team are also part of an international research team, led by Dr. Trevor Crowell, the director of the Clinical Research Directorate at the Military HIV Research Program, evaluating the interplay of HIV, COVID-19 and neurobehavioral health. This second NIMH-sponsored study is supported by a total grant of $3,822,251.

The researchers are making use of very large sets of clinical data acquired in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Nigeria and Thailand to understand the social, cultural, financial and healthcare system-related barriers that emerged during the different waves of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the consequences to mental and physical health associated with disruptions limiting access to care for people around the world, particularly in resource-limited settings. They are also targeting pre-infection to post-infection problems with mental health. Paul and his team work closely with the data coordinating center at MHRP to harmonize data acquired in the individual cohorts to foster discovery of new insights regarding the HIV-COVID-19 syndemic.

Paul’s team brings particular expertise in using neuroimaging to quantify and visualize damage caused by HIV and COVID-19 on brain structure and function. The MIMH team is also recognized internationally for the application of machine learning methods – i.e. artificial intelligence – from the data science field to discover the presence of distinct risk profiles needed to inform the development of therapeutic strategies.

“We believe with the methods that we use and the data that we have available to us, we have an opportunity to create a decision tool for clinicians to facilitate early identification of individuals who are at risk for persistent immune and brain abnormalities associated with HIV and COVID-19 infection,” Paul said. “The work has important clinical significance because the combination of viral, immune and psychosocial and cultural factors that identify distinct individual health outcomes following HIV or COVID-19 infection is a critical step towards designing and implementing clinical strategies that can be tailored to individual risk profiles. That is the ultimate goal for precision health research.”