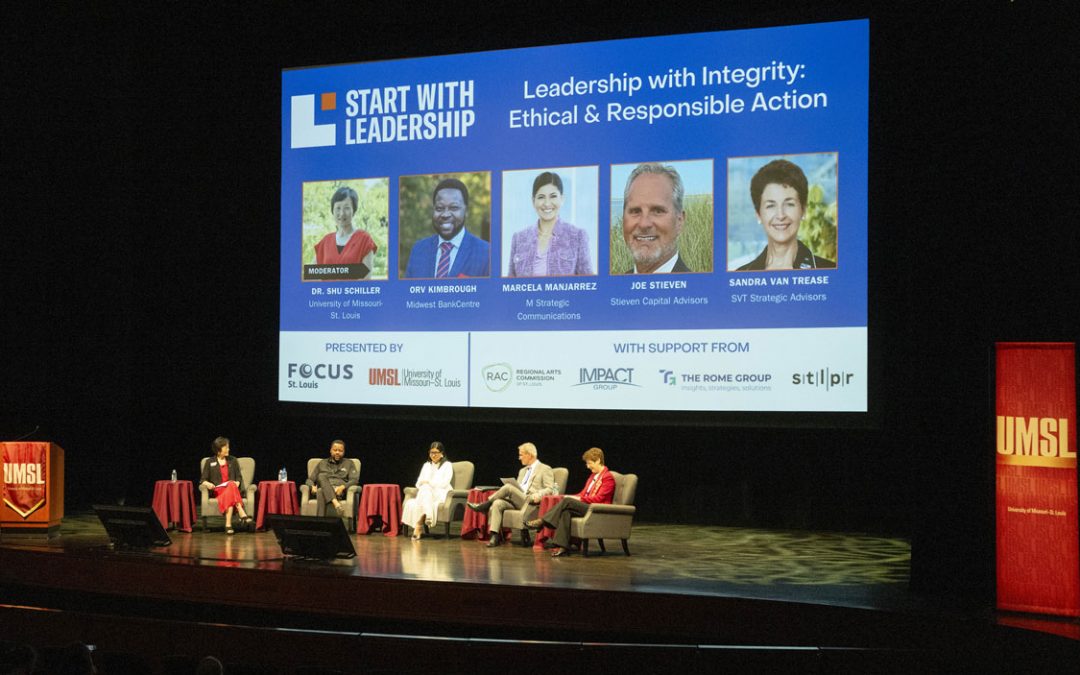

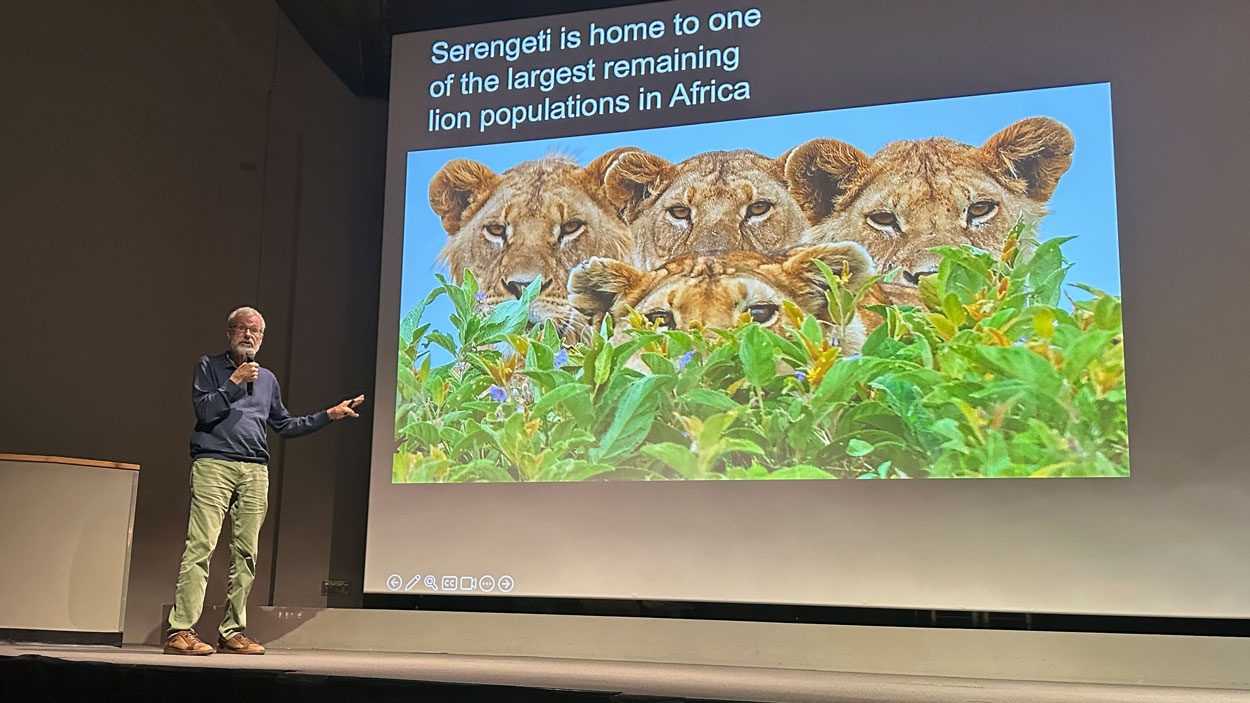

Craig Packer, the director of The Lion Center at the University of Minnesota, delivers the 2025 Jane and Whitney Harris Lecture in The Living World at the Saint Louis Zoo. Packer has spent five decades researching lions and contributing to conservation efforts, with much of his work done in the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania. (Photos by Steve Walentik)

Craig Packer has spent the past five decades researching lions and learning everything he can about them.

Back when he started, Packer, the Distinguished McKnight University Professor and director of The Lion Center at the University of Minnesota, would give talks focused mainly on the defining characteristics and behavior of Africa’s top predator, often making comparisons to other cats such as tigers and leopards.

“They were the Drosophila” – or fruit fly – “of big cats, and you could do basic research on them, and you didn’t have to be worried too much about saving them,” Packer said last Tuesday as he delivered the biennial Jane and Whitney Harris Lecture to an audience of more than 50 people at the Anheuser-Busch Theater in The Living World at the Saint Louis Zoo.

That’s no longer the case. An animal that centuries ago could be found roaming the land from Europe to the southern tip of Africa and stretching from the continent’s western coast all the way to India now occupies less than 10% of that historical range. The global population of lions has decreased by about 75% in the past 50 years. They are extinct in 26 African countries, and the northern subspecies is considered endangered with the western clade critically endangered. The southern lion, meanwhile, remains vulnerable with the loss of habitat posing a significant challenge to its survival.

“We’ve had to confront the fact that we have to do something to help protect the species into the future,” Packer said while speaking as a guest of the Whitney R. Harris World Ecology Center at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

The Jane and Whitney Harris Lecture Series was created to bring in experts from around the country to share their knowledge and experiences with students and the wider community. It fits with the Harris Center’s vision to reverse the trend of biodiversity loss through community education, research and the training of students who go on to contribute to conversation around the globe.

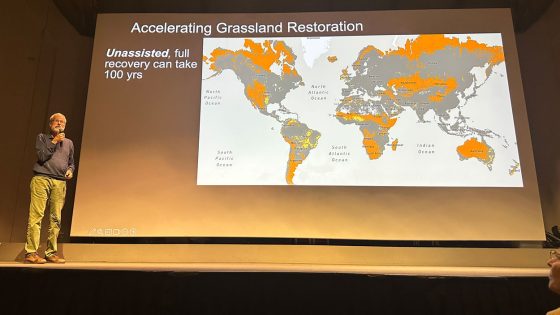

Craig Packer discussed the importance of grassland restoration in conserving the population of lions in Africa during the Jane and Whitney Harris Lecture.

Over the course of his more than hour-long talk, Packer, best known for his research on lions in Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, discussed efforts to protect the species through captive management, regulations on sport hunting, protection against infectious disease and, most critically, human-lion interaction.

Packer doesn’t dismiss the importance of zoos and other sanctuaries for their role helping preserve the species.

“These are actually really important repositories, in case the worst happens in these wild areas, to keep the species going,” he said. “But you have a problem because when you’re trying to construct a social group in captivity, these are very territorial animals. One of the things that we’re finding is that, particularly with rescue programs, that lions are being rescued from circuses and roadside zoos, and these poor things have been kept in small cages, hardly able to move, and they’ve been kept alone, so they don’t know how to interact with other lions.”

Packer described how a big cat sanctuary in South Africa called LIONSROCK has gone about helping socialize lions using the hormone oxytocin, which is released naturally when lions interact within their family structure.

In the wild, lions face threats from sport hunters as well as from disease. Packer has done research that has helped inform policy solutions for both.

His work showed the impact restrictions on the age at which males can be hunted can have on the health of the population because, by allowing males to reach at least the age of 6, they have a chance to reach full maturity, establish themselves within a pride and have offspring that can survive through the first two years of their lives – when they’re most vulnerable and at risk of being killed by other males. Countries such as Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe have set restrictions that align with Packer’s guidance.

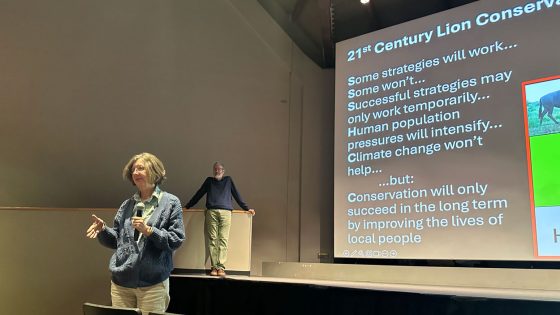

Susan James, the wife of Craig Packer, fields a question about efforts to engage local communities in conservation during the Jane and Whitney Harris Lecture. James helped found Savannas Forever Tanzania, a nonprofit organization that specializes in data collection that helps support the evaluation of development projects in Tanzanian villages.

Another study demonstrated the impact vaccinating domestic dogs could have protecting lions from diseases such as canine distemper virus and rabies.

“No organism exists in isolation,” said Nathan Muchhala, an associate professor of biology at UMSL and the interim co-director of the Harris Center. “It is also being hit by these biodiversity crises around the world.”

Indeed, Packer spent the largest part of his lecture discussing how restoration of their grassland habitat would do the most to positively affect lion conservation.

The savannas that lions call home are under significant strain from overgrazing by livestock, particularly cattle that humans such as the Maasai depend on for survival. That creates challenges for the populations of large herbivores that depend on the same edible biomass for their food. Lions, in turn, feast on those large mammals.

“With so much pressure on the savanna ecosystems, you’re starting to see severe habitat degradation,” Packer said. “You’re seeing erosion, species loss in plants. That ultimately is going to reduce the number of herbivores – wild herbivores – and that further reduces the number of carnivores. So, going up the pyramid, everything that’s affecting the amount of plants that are available for lions’ prey are being reduced, and that’s going to reduce the number of carnivores the system can support.”

Packer and his wife, Susan James, helped found Savannas Forever Tanzania, a nonprofit organization that specializes in data collection that helps support the evaluation of development projects in Tanzanian villages. Those communities have been able to use relevant data to design appropriate responses to a variety of agricultural and conservation issues, as well as ones related to human nutrition, health and economic wellbeing.