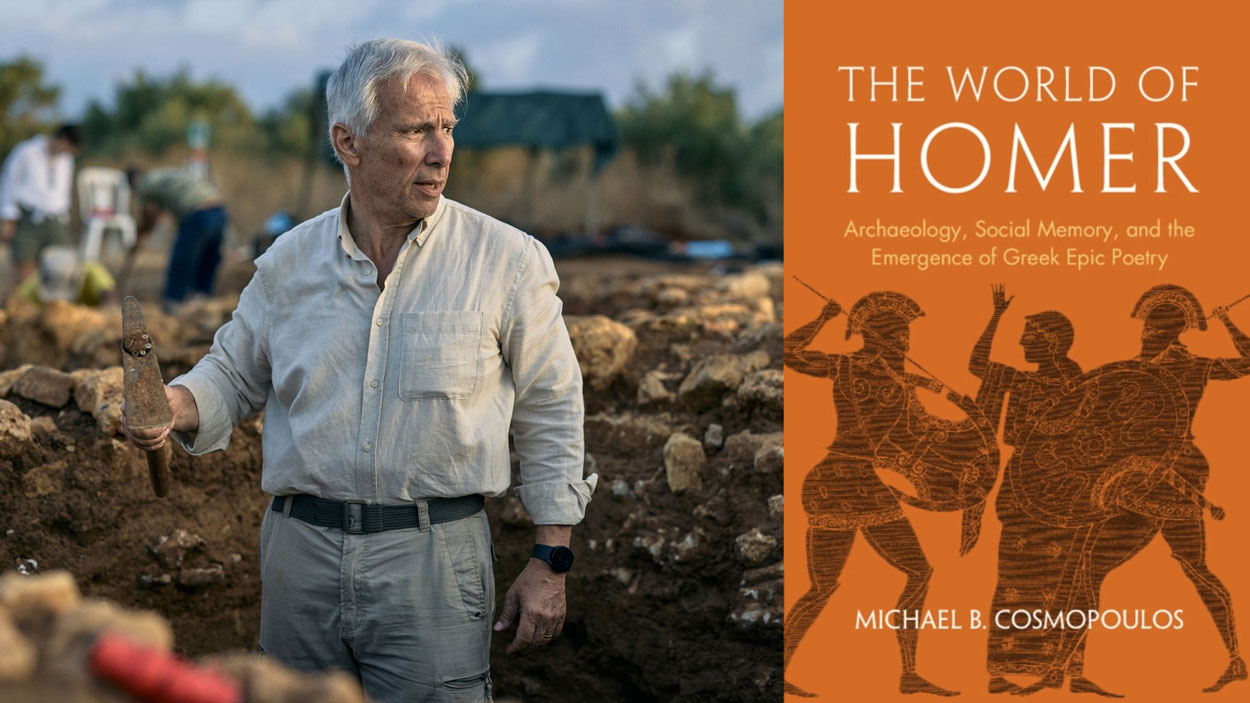

Michael Cosmopoulos, the Hellenic Government-Karakas Foundation Professor of Greek Studies at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, is the author of a new book, “The World of Homer,” which explores the many forces, historical, social and poetic, that gave rise to the epic poems “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey.” (Photo courtesy of Michael Cosmopoulos)

Michael Cosmopoulos is back in Greece this summer, continuing his ongoing work at the excavation of the Late Bronze Age Mycenaean city of Iklaina.

But Cosmopoulos, the Hellenic Government-Karakas Foundation Professor of Greek Studies and professor of archaeology at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, has also been sharing the results of another deep dive into the past with the publication of his new book, “The World of Homer.”

The book, from Cambridge University Press, was released in the United Kingdom earlier this month and will debut stateside in August. It explores the epic poems “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” and wrestles with the debate over their origins, including whether they can be traced to a single era and author – i.e. Homer – or, far more likely, were developed over centuries by many poets while shared through oral tradition.

Cosmopoulos, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, who last year was inducted into the Academy of Athens as Chair of Bronze Age Archaeology, uses his expertise in archaeology and anthropology as well as philology to help readers understand the world in which the poems were formed and the factors that shaped them into works that continue to be celebrated in the modern day.

In a Q&A with UMSL Daily, Cosmopoulos discussed what has long captivated him about the epic poems, what inspired him to dig into their origins and why it matters for readers now.

When did you first read the Iliad and the Odyssey?

My connection with “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” began in childhood, through Greek myths and the ancient ruins that surrounded us growing up in Athens. Then, in high school, like all Greek students, I studied the poems in the original Ancient Greek and was captivated by the power of the stories and the rhythm of the poetry.

What impact did they have on you when you read them?

They were nothing short of mesmerizing. From the very beginning, the larger-than-life heroes, the fierce battles, the importance of honor and the uncertainty of fate transported me to a world that felt both distant and strangely familiar. Looking back, even then I think I was sensing that these works emerged from something older and deeper than literary imagination alone, something rooted in collective memory and cultural experience.

When did you start thinking more deeply about their origins?

That began during my university years, especially when I turned to Bronze Age archaeology. As I studied and excavated sites like Mycenae, Ithaca, Pylos and later Eleusis and Iklaina, I began to see connections between the material remains of ancient Greek societies and the poetic world of Homer. The more I learned, the more I realized that understanding “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” was vital to uncovering the historical and cultural realities of the world that produced them.

What made you want to dig into who Homer was and how the poems came into being?

It was the mystery of their authorship and of the processes of their creation. How could poems of such magnitude (“The Iliad” is about 16,000 lines and “The Odyssey” 12,000) have been created in a preliterate society? Was Homer real or a symbolic figure standing for poets whose names have been lost to the ages? How did the ancient Greeks remember and transmit these stories? And what role did archaeological remains and social memory play in shaping them? These questions stayed with me and grew stronger over time. I wanted to understand the mechanics and circumstances of epic creation, not just the content. In the end, the evidence points to one inescapable conclusion, that the poems were not created by one, but by many “Homers.”

Why does it matter how these poems were created?

Understanding their creation helps us understand the origins of our own civilization, how the people who came before us saw their past and their present, how they preserved memory and how they gave voice to their values and fears through poetry. In doing so, we also gain insight into the power of storytelling to shape identity across time. The wider picture is that these two epics help us understand human nature, from the devastating impact of war and violence on human character to the appreciation of the journey of life. These are not values disconnected from us in time and in space but universal values that can help us navigate the challenges of today’s world.

When did you start working on this project, and when did you know that it would become a book?

Throughout my academic career, every few years I taught a course on the Homeric epics. With every lecture and every class discussion, I found myself increasingly captivated by the insights into the human experience that the epics convey. The idea for this book started to brew in one of those classes, but I remained hesitant, fully aware of the all-consuming vortex that such a project would create. Then, during my fieldwork at Eleusis and Iklaina, the threads connecting myths, monuments and memory started to become increasingly clear. Ultimately, the desire to explore these connections in depth and systematically became too compelling to ignore, and I found myself putting pen to paper, trying to give concrete form to the ideas that had been percolating in my mind for a long time.

What has captivated you most about the things you discovered in your research?

It is the realization that these poems were not composed in a vacuum. They are the product of a long and complex process blending historical memory, mythological tradition, oral composition and performance. The idea that elements from the Late Bronze Age could survive the collapse of the Mycenaean world around 1200 B.C. and find their way into oral traditions that crystallized centuries later was both fascinating and humbling. The epics are layered, and through those layers, we glimpse the evolution of Greek identity and storytelling.

How does digging into the past in this way compare to doing so as part of an archaeological excavation?

In both cases, you are reconstructing something that no longer exists in full. As an archaeologist, you excavate layers of earth; with Homer, you excavate layers of memory and tradition. But in both, you deal with fragments, potsherds and ruins on one hand, verses and formulas on the other. Each offers different kinds of evidence, but both are necessary to understand how the epics were created.

What do you hope readers will take away from “The World of Homer?”

I hope readers come away with a deeper understanding of how “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” came into being – not as the creation of a single genius but as the outcome of a centuries-long process involving oral performance, collective memory and cultural continuity. The goal is not to “solve” Homer but to appreciate the many forces, historical, social, and poetic, that gave rise to these masterpieces.

At the same time, we live in a time when the very qualities that make us human, from our capacity for empathy and our ability to uphold moral principles to our need for reflection, connection with others, and meaningful expression, are increasingly marginalized in the pursuit of technological efficiency and economic gain. In this environment, “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” are powerful reminders of what it means to be human. They were born out of a need to make sense of suffering, to honor memory, to give voice to loss, courage, love, and the longing for home. By exploring how these poems were shaped over the course of generations by real people in response to real human experiences, we reconnect with the fundamental values that define us and that we risk losing if we forget them.