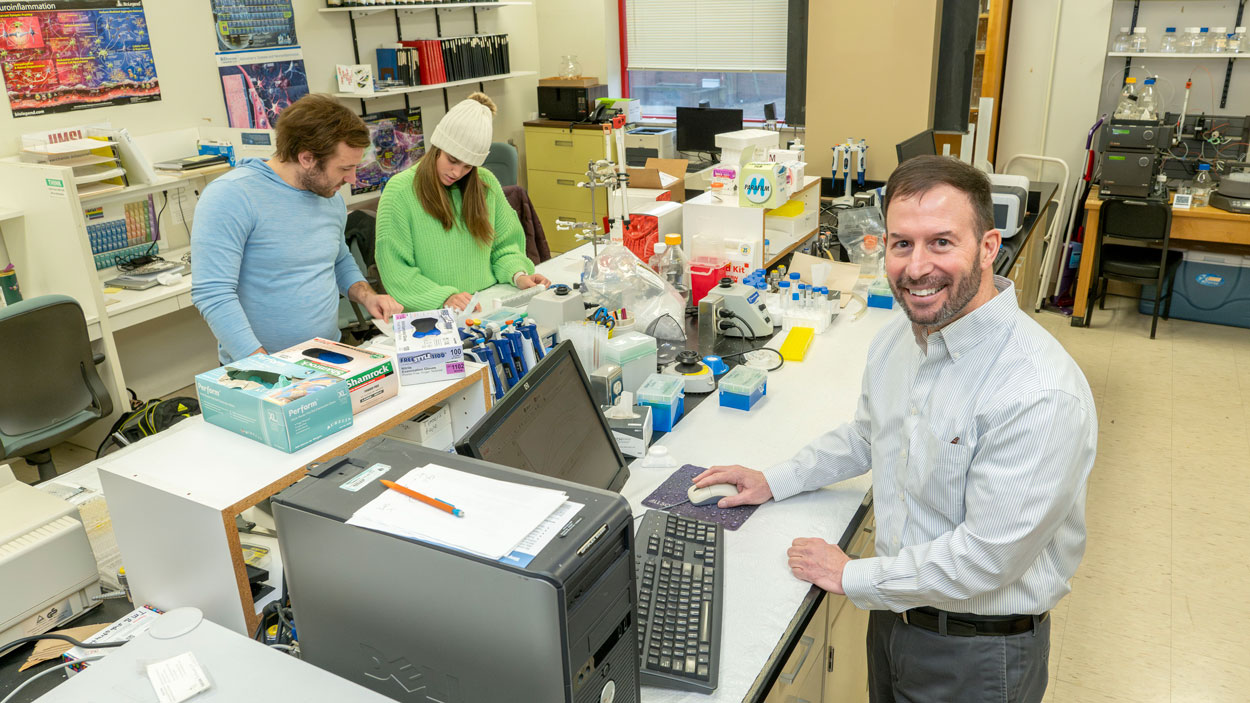

Professor Michael Nichols (at right) received a $459,279 grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences to study the mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation associated with inflammation that occurs in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients. (Photos by Derik Holtmann)

Michael Nichols has spent more than two decades exploring the chemical imbalances in the human brain associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Nichols, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Missouri–St. Louis and the director of its biochemistry and biotechnology program, has focused his research on the inflammation in the brain that occurs as part of the neurodegenerative disorder. He hopes to understand what causes it – and how – so that one day there might be a therapeutic developed to prevent the disease.

Since arriving at UMSL in 2004, he has published his research findings in journals such as Neuroscience, Nature Medicine and the Journal of Neurochemistry.

UMSL Professor Michael Nichols (at left) stands with members of his research team (from left) Cristina Sinobas Pereira, Noor Yousaf, Ryan Domalewski, Samir Benbakir and Nathan Zeller. Nichols’ lab is doing work related to Alzheimer’s disease.

Nichols is building on that work over the past 20 years with the support of a new, $459,279 grant awarded last fall from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health. He is studying the mechanisms with which the amyloid-β protein – commonly referred to as Aβ and believed to play a central role in Alzheimer’s disease – activates a group of three proteins known as NLRP3 inflammasome to cause inflammation inside immune cells in the brain. Supporting Nichols is a research team that includes graduate research assistants Ryan Domalewski, Samir Benbakir, Cristina Sinobas Pereira and Nathan Zeller and undergraduate Noor Yousaf.

“We all know that Aβ can activate this complex,” Nichols said. “The question is how? That’s why the title of our NIH project is: ‘Mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation.’

“Our hypothesis is that Aβ can get inside the cells – and we’ve already shown that in other studies – and interact directly with this protein complex, NLRP3 inflammasome. Others have shown that Aβ activates through other indirect pathways, in which something downstream then activates the proteins. Both can be true, and it would be a big achievement to show that this direct interaction occurs and plays a role in impacting inflammation because then we can possibly find ways to block it.”

Any chronic inflammation can be detrimental, particularly in the brain.

An important part of the inflammation results from the production of another protein called interleukin-1β when NLRP3 inflammasome is activated. The IL-1β builds up in the cells and can be toxic to healthy neurons.

It’s been established that Alzheimer’s patients have higher levels of IL-1β, but the research could have implications for the treatment of other inflammatory diseases as well.

“There are other molecules and other non-central nervous system diseases like cardiovascular disease that involve this complex,” Nichols said. “How those molecules in that disease activate this complex is of interest. If it’s a general mechanism, researchers should consider this as a target. But if it’s specific for Alzheimer’s and this amyloid-β protein, that’s OK too. At least you know that there’s some specificity between diseases.”

Nichols, who is currently serving as the president of the American Society for Neurochemistry, was ahead of a lot of other researchers in focusing his attention on inflammation associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

With a background in neurochemistry as a doctoral student at Purdue University, he became curious about the relationship while reading journal articles as a postdoctoral fellow at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida. When he came to UMSL, he decided to make it a central component of his research.

“Not very many people were focused on inflammation at the time,” he said. “It was kind of a little niche that we were trying to carve out. Over the course of 20 years, now everyone is paying attention to inflammation in the brain and its role in Alzheimer’s disease. The good thing is, there’s a lot more interest scientifically in it. But there are a lot of researchers also trying to study this.”

Each new breakthrough is built upon past discoveries.

Nichols’ latest grant will help fund his research until 2026. He is interested in expanding the project to incorporate the use of human stem cells, which can now be obtained from skin cells and converted into brain immune cells to better replicate the biochemical interaction that is occurring in Alzheimer’s patients.

In the future, he’d like to explore what about the immune system and immune cells makes some people more resistant to Alzheimer’s disease than others.

“I’m interested in that as well,” Nichols said, “trying to see what makes some people protected against Alzheimer’s disease.”