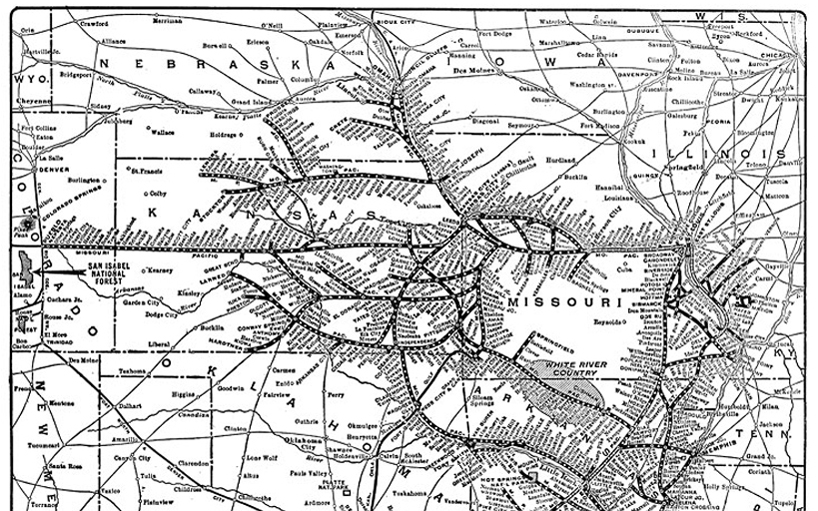

The Missouri Pacific, originally the Pacific Railroad of Missouri, was one of the first railroads in the United States west of the Mississippi River. (Detail of MoPac System Map courtesy St. Louis Mercantile Library)

The interconnected history of St. Louis, railroads and commerce has led Carlos Schwantes, the St. Louis Mercantile Library Endowed Professor in Transportation Studies, on a lifelong journey of discovery.

These topics are also the focus of an upcoming talk that Schwantes will give at 2 p.m. Sept. 21. Part of the Mercantile Library’s speaker series in commemoration of the 250 years since St. Louis’ founding in 1764, the event is free to University of Missouri–St. Louis students, $10 for library association members and $12 for non-members. (More information on the library’s events and exhibitions is available here.)

In anticipation of his presentation, Schwantes spoke with UMSL Daily, offering a sneak peek at his topic “Opportunity Reborn: When St. Louis Reoriented its Compass of Opportunity during the 1870s and 1880s.”

The title of your lecture suggests that the 1870s and 1880s were a pivotal time for St. Louis. What was at stake?

Quite a bit, actually. For virtually all of the city’s history until the mid-1850s, the merchants of St. Louis had looked north, northwest and west as they enlarged the boundaries of the city’s commercial empire along the great waterways. The coming of the first steamboat to St. Louis in 1817 greatly aided their efforts and helped to bring a wave of prosperity to the city. Beginning in the 1850s, a new technology – the railroad – gave a big boost to its much younger rival, Chicago, which had no vested interest in steamboat-based commerce and was eager to use the railroad to enlarge its own empire.

By the mid-1850s, a railroad running west from Chicago sliced directly across one of the great waterways long claimed by St. Louis merchants – the Mississippi River – at Rock Island, Ill. And that was only the first of many cases of Chicago railroads redirecting the commerce that once flowed along the waterways.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the commercial leaders of St. Louis were concerned about their city’s future. Reorienting the compass of opportunity to the Southwest was the foremost task of several St. Louis-based railroads that extended lines from St. Louis to take advantage of new economic opportunities emerging in Texas.

Does the shift in St. Louis’ “compass of opportunity” during that period offer lessons for navigating today’s challenges?

Quite an interesting lesson, in fact. I relocated to St. Louis in 2001, and during the years since then I’ve witnessed something quite similar to what took place in the 1850s and 1860s between Chicago and St. Louis. Chicago has gained in terms of commercial air connections, which essentially form the nerves of modern global commerce. In 2001, St. Louis was the global hub for TWA, and thus the city had a variety of nonstop flights to places like London and Rome. Now St. Louis has no such connections and is at an aviation disadvantage in the age of global commerce. Can that be changed? Yes, but we need the municipal will to do so, as the city had in the 1870s and 1880s.

Beyond the Mercantile Library with its invaluable collections related to the history of transportation and the West, where else does your research on railroads and related topics take you?

Good question. My search has taken me to a variety of research centers, including the archives of the Chicago Historical Center. But I am also a big believer in what I call “history of the hoof” – going and seeing for myself where history took place.

Last October, I took an Amtrak train from San Antonio to St. Louis along the route of a pioneer railroad connecting St. Louis and Texas – the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern, which extended tracks through Arkansas to do its part in reorienting the compass of opportunity for St. Louis and for Texas, too. I think it’s safe to claim that for many years St. Louis was the effective “capital” of Texas, and I will back this up in my presentation.

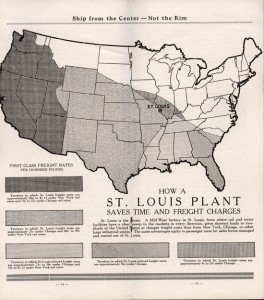

I’ve amassed a huge archive of 19th-century railroad promotional material, much of it filled with amazing graphics that illustrate what took place. I purchased virtually all of this on eBay, watching especially hard for items that spoke to the history of St. Louis. That was the “thrill of the hunt.”

What have you found most engaging about your areas of inquiry?

As I often say to my students, having fun with history is serious business. I have enjoyed researching this topic and repeatedly discovering connections that make seemingly separate events and people part of a large, interconnected and thoroughly fascinating aspect of St. Louis history.

Building my own collection of St. Louis historical ephemera, items that most people once considered throwaway pamphlets and tracts such as the vintage railroad promotional brochures and timetables, has been very satisfying. I’m delighted to be able to draw now on my own growing archival collection for many of the illustrations in my upcoming presentation.