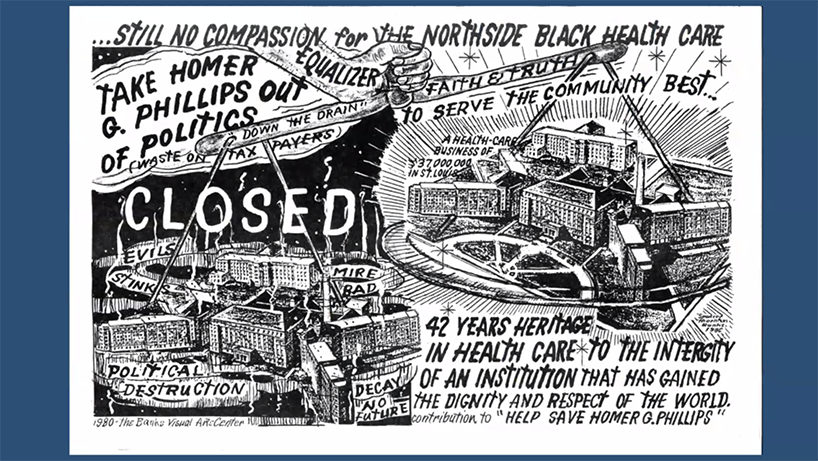

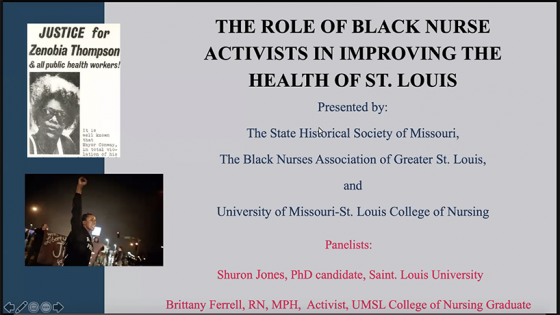

Shuron Jones shared this political cartoon opposing the closure of Homer G. Phillips Hospital during Friday’s “The Role of Black Nursing Activists in Improving the Health of St. Louis,” which also featured UMSL alumna Brittany Ferrell. The Black History Month event was presented collaboratively by the UMSL College of Nursing, the State Historical Society of Missouri and the Black Nurses Association of Greater St. Louis. (Screen shots of presentation slides)

When she was serving as president of the Minority Student Nurses Association, then-University of Missouri–St. Louis student Brittany Ferrell began wondering why MSNA existed. There was another College of Nursing student group, the Student Nurses Association, after all.

Why did there need to be two student associations?

“The lived experiences of Black students and students of color were so unique that we did need a space to be able to support one another and to really be able to talk about some of the issues that impact our communities,” Ferrell said.

Her realization proved to be the first catalyst on Ferrell’s path toward becoming an activist fighting for equity and health care equity for the Black community and for St. Louis. Her story was one of two highlighted during Friday’s virtual Black History Month event “The Role of Black Nursing Activists in Improving the Health of St. Louis.”

Presented in conjunction with the State Historical Society of Missouri and the Black Nurses Association of Greater St. Louis, the event was moderated by UMSL Associate Professor of Nursing Wilma Calvert and SHSMO Senior Archivist A.J. Medlock, and it juxtaposed historical and modern examples of Black nurse activism.

In addition to Ferrell’s story, the panel discussion also featured Shuron Jones, an UMSL alumna and history instructor and PhD candidate at St. Louis University. She discussed Zenobia Thompson, a 1970s-era nurse activist working to oppose the closure of Homer G. Phillips Hospital, the only public hospital serving the Black community in St. Louis and training Black practitioners.

Shuron Jones, Zenobia Thompson and the Homer G. Phillips Hospital

Jones began her talk by pointing out the great historical contribution of nurses fighting for Black equity and freedom, from working with organizations such as the NAACP in the effort for voting rights to forming the National Black Nurses Association and working toward equitable health outcomes to individuals such as Thompson.

Thompson’s activism, which she called her “progressive consciousness” came from her background and experiences. Born in 1944 in Wayne, Arkansas, Thompson moved to St. Louis as a child. As a junior in high school, she began working as a “tray girl” at Barnes Hospital and tried to enter nursing school at that facility.

Rejected because she was Black, Thompson decided to attend the Homer G. Phillips Hospital School of Nursing.

“During college, Zenobia described herself as going from an ugly duckling to a swan,” Jones said. “She started to espouse some political consciousness, and some of it was around feminism.”

Thompson devoted herself to her studies – instead of working to find a husband – becoming “quickly rebellious.” She graduated and began working in pediatrics and obstetrics at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, where she faced frequent racism that ultimately led to her being fired after seven years. She returned to Homer G. Phillips, eventually becoming a head nurse.

“Since the inception of the hospital, politicians specifically and bureaucrats in St. Louis City have attempted to close it,” Jones said, explaining that then-Mayor Jim Conway became the driving force behind the closure, though it was the broken promise of his successor, Vincent Schoemehl, that sealed its fate.

Despite opposition from activists such as Thompson, the hospital closed in 1979 and was eventually converted into a senior living facility.

Brittany Ferrell’s activism develops through Ferguson uprising

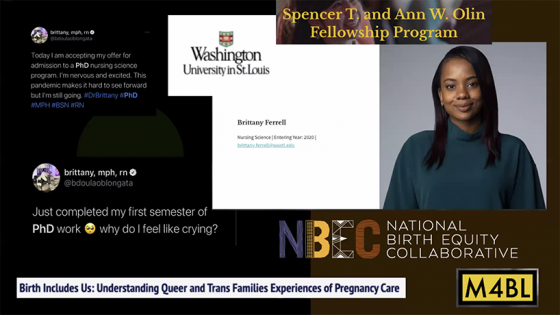

Ferrell had almost completed UMSL’s BSN program when Michael Brown was killed in nearby Ferguson, Missouri. She made the decision to drop out of school and become a full-time activist, eventually returning to finish her degree and going on to Washington University in St. Louis to earn a Master’s of Public Health and is now working on a PhD.

Ferrell pointed to the long history of Black nurses as activists and patient advocates “being a voice for the vulnerable.”

“The Ferguson uprising was, in so many ways, the origins of the shift that needed to be for us to be able to talk about some more difficult and complex things that oftentimes makes us uncomfortable around race and equity and the mistreatment and disproportionate risks and criminalization and harm that’s caused to Black communities,” Ferrell said. “…I felt called to do something. I had to do something. I had to make a decision, and I chose to be in the community with the people, and I do not regret it at all because it really informed my community approach to health and public health.

After earning her BSN, Ferrell began working in medical oncology, orthopedic care and finally labor and delivery, falling in love with the practice but also witnessing deep problems.

Driven to make a difference and gain more deep knowledge, she stepped away from clinical practice.

“That has led me down a path to really connect activism and to connect nursing and public health together so that we are able to stand in the legacy of what nursing truly is,” Ferrell said.

Now as a PhD student, she’s studying both chronic stress and the implications of stress on pregnancy and birth outcomes as well as queer and trans families’ experiences of pregnancy care.

She’s also working on a documentary “You Lucky You Got A Mama,” which includes the pregnancy and childbirth experiences of Black female, trans and gender-fluid peoples in the U.S.

In addition to the struggles, Ferrell is devoted to including happy endings and solutions, such as alternatives to traditional hospital experiences such as midwives and doulas.

“Black women and birthing people, we have to save our own lives,” Ferrell said. “…that’s my journey. That’s what I’m working on. That’s my life.”