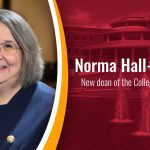

Associate professors of communication Alice Hall (left) and Lara Zwarun are doing at least 13 tasks between them. How many can you find? (Photo by August Jennewein)

When it comes to the Millennial generation, multitasking with technology is as ubiquitous as Ugg boots and skinny jeans.

Visit any college campus, and you’ll see figures furiously thumb-typing on their phones, using ear buds to pipe in their own personal soundtrack, sipping lattes and carrying on conversations at the same time.

But Millennials aren’t the only people multitasking, and doing multiple things at once might not be as distracting as it’s often reputed to, according to a new study by University of Missouri–St. Louis researchers Lara Zwarun and Alice Hall.

People who multitask while answering survey questions skew toward both the older and younger ranges of the age spectrum, and most report feeling comfortable and not distracted, according to the research. The report, “What’s going on? Age, distraction and multi-tasking during online survey taking,” was published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior.

“I think there is something to the idea that younger people are more comfortable with it because they do overall seem to multitask more, but there do seem to be some heavy multitaskers in the older age range that are quite confident,” said Zwarun, associate professor of communication at UMSL.

Nearly 6,000 people from seven countries responded to the UMSL pair’s survey. Participants were those who had already participated in an online survey distributed by an international market research company. Once they finished the regular survey, Zwarun and Hall’s questions asked what sort of other tasks they were doing while answering the questions.

Tasks were divided into environmental distractions, such as music playing or people talking in the background; nonelectronic multitasking, such as respondents getting up from the computer or talking to someone else; and electronic multitasking, such as talking on the phone or responding to a text. Respondents explained which other tasks they were doing and how distracted they felt.

Seventy percent of those questioned responded they were doing nothing else while taking the survey, but it was the remaining 30 percent that most interested the researchers.

Respondents in all age groups, from 18 to those over 65, reported they were multitasking, but different age groups reported varying levels of comfort and distraction. Younger respondents and older respondents were most likely to feel competent answering questions while distracted, but those who were middle aged reported feeling the most frazzled.

As for the middle age, it’s likely that people who have family and work obligations are going to feel the most distracted.

“I think it’s probably a function of having a lot going on in life,” Zwarun said. “I don’t know that it’s necessarily a cognitive thing where at one age your brain loses the ability to multitask and then gains it back.”

The next step for the researchers is to try to gauge how multitasking impacts performance.

Multitasking often has a negative connotation, implying that task-doers are less effective when they’re attempting multiple things at once, therefore not really paying attention to any of them.

The study has implications for researchers who use surveys to gauge public opinion or do other research, said Hall, associate professor of communication at UMSL. Researchers need to understand that in the real world, their participants may have distractions, such as a ringing phone, interrupting child or arriving text message.

“Something could happen that is going to pull them away from the initial task,” Hall said. “In some cases that’s just fine. You want to see how the commercial that you’re showing or whatever it is functions in real world environment. If you’re looking at something that requires sustained concentration you would need to take into account what else is going on in the participant’s environment.”