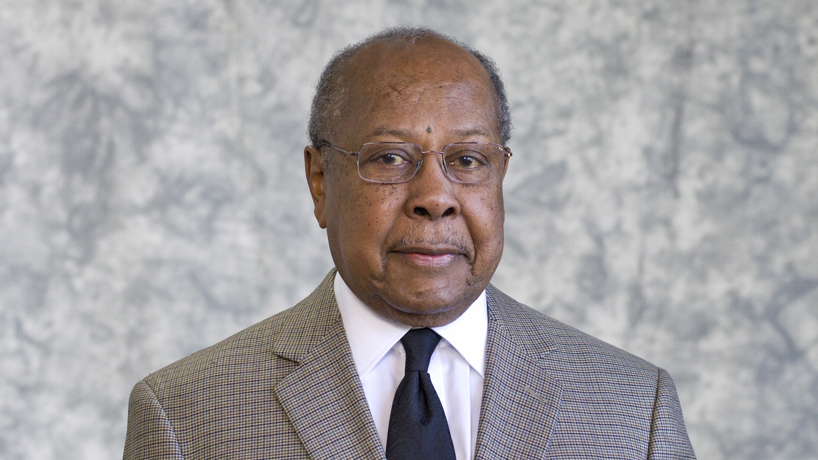

(Photo by August Jennewein)

Adell Patton likes to say he came up from the ashes as a native of the Arkansas Delta. Intrigued, UMSL Daily caught up with the Founders Professor of History at the University of Missouri–St. Louis to explore his own history in the midst of his 20th year with UMSL.

Patton’s mother and father, who couldn’t read or write, worked as sharecroppers in Haynes, Ark. His circumstances were so humble that one night his parents checked on Patton in the middle of the night. By the light of a coal fire lamp, they saw a rat gnawing on their infant son’s head.

Though the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued 70 years before his birth, Patton said he grew up on what he calls a new kind of plantation for a new kind slavery. The school year was different for white children than for black children. The white children’s school had an August to May schedule that would be familiar today. For kids like Patton, there were long breaks in April and then again in September so that they could work in the fields for planting and harvest.

He recalls the owner of the land his parents sharecropped telling him, “Boy, I want you to grow up now, because I got a house for you out there and I want you get married and have some children.”

Patton said the land owner was just making explicit what the school system implied: that people like Patton belonged in the fields, not in school – and certainly weren’t supposed to ever leave Haynes. There was also the nascent black bourgeoisie of Forrest City who, in Patton’s words, engaged in the selection of who would and who wouldn’t “make it.” Patton was told he was not selected.

In the fields, Patton picked cotton “from can’t to can’t,” which is to say his day both started and ended when he couldn’t see. If the sun was in the sky, he was working. He picked a bale of cotton a week, 1,200 pounds a year. He was paid only a tenth of what he estimates that his boss pocketed from that labor. In all his childhood, Patton never saw a white person doing the kind of work he did.

Patton’s parents wanted him educated because he had chronic asthma, meaning that a life of farming was not possible for him.

Lucky for Patton, his hard work and the hard work of his family got him to Kentucky State University after he graduated from high school in 1955. And he was a college freshman before he learned the elite of his hometown never expected him to make anything of himself. At Kentucky State, he studied the trumpet, aiming to be the next Miles Davis.

That he was not, but he did graduate from Kentucky State in 1959 with a bachelor’s degree in music education. Patton said he had a chip on his shoulder courtesy of all those from his childhood who had tried to keep him “in his place.” He had plenty of drive, but he did not yet have an interest in history. In 1960 he joined the U.S. Army and, after training at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., found himself headed to Fort Gordon in Augusta, Ga., and the Naval School of Music.

Patton’s time at Fort Gordon was his first integrated experience. Enlisted men of all races were in the same barracks, and Patton was also housed with descendants of both the Confederacy and the Union. The two factions constantly rehashed that hundred-year-old war.

“Every day they were fighting the Civil War,” Patton said. “One guy would say, ‘You only won because you had all the railroads.’ Another guy might respond, ‘Well, you might have won if you’d just let those slaves go.’ Meanwhile, I’d just sit on my bunk listening to them, not saying anything.”

Though the experience with his fellow soldiers sparked an interest for history within Patton, it wasn’t until an incident later on during his time in the Army that he felt absolutely compelled to take up the discipline.

One day, several thousand soldiers from Fort Gordon filled an auditorium to hear a chaplain speak. The man announced to the crowd that he would write a quotation down on a piece of paper and then pass it through the crowd. He instructed those gathered to sign their name to the paper if they agreed with the quote.

Recalling the incident, Patton stresses that one must understand this was the height of the Cold War. In Patton’s words, the Ku Klux Klan had taken off their sheets and put on Armani suits and formed White Citizens’ Councils. McCarthyism was rampant, as was the John Birch Society. The authorities were on the lookout for Communists and eager to stamp out anything that might be construed as dissent.

When the piece of paper made its way to Patton’s friend Searcey, Patton asked him what it said.

“I don’t know,” Searcey replied. “It seems to me they want to know if you want to overthrow the government.”

Given the political climate at the time, Patton didn’t need to know anything else about what the paper said. He passed it along without reading. A few minutes later, the chaplain announced that the paper had made its way around the room, and he read the quote aloud: “If someone attempts to usurp the powers of your government, you have the right to step up and overthrow it.”

The chaplain said the quote paraphrased lines found in the Declaration of Independence. A total of three people had signed their names. He dismissed the crowd, and Patton said he wanted to hide under his seat he felt so ignorant. Afterward, he headed straight for the Army extension center and asked for a correspondence course in colonial American history to 1865.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Patton went on to earn a master’s degree in U.S. history and government from Butler University and a doctorate in African history from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Before coming to UMSL he was a professor at Howard University in Washington, D.C. A professor of history for more than 40 years, Patton retired from UMSL in August. He will serve as a UMSL Founders Professor until 2017.

Despite all his accomplishments, Patton is adamant that he still has much to do.

“I’m always looking around for sparks to push me forward,” he said.

This story was written by alumnus Ryan Krull, MFA 2014, a student support specialist who also teaches writing courses at UMSL.