This artwork was one of many artistic expressions painted on the plywood of boarded up businesses on Florissant Road. (Photos by August Jennewein)

The death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., on Aug. 9 changed the St. Louis region forever. Among expressions of grief and protests came riots, arson and clashes between law enforcement and citizens as issues of racism, discrimination and police use of force became prominent. Ferguson, the suburb that lies less than 1,000 yards from the University of Missouri–St. Louis campus, quickly gained international attention.

The UMSL campus hosted civil dialogue and many students, faculty and staff took action as protests continued through fall and winter.

We’ve collected some of their stories here. Their voices are different, but each has a desire for the region to understand, heal and move forward.

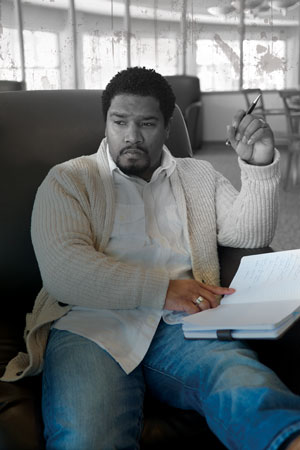

Jason Vasser, poet and art activist

Jason Vasser left work one day at Student Retention Services and drove up Florissant Road where he spotted a group picking up trash in a parking lot. He knew what the news reports said but wanted to see for himself what was happening along the road where protesters, police officers and rioters were clashing a few miles from the UMSL campus.

Vasser stopped, grabbed a bag and joined them. The experience was the inspiration for his poem “Picking Up in Ferguson.”

“I would see images on TV where it would be the police force against the people, or showing white people against black people, but picking up trash, it was people of all different nationalities,” Vasser says. “We may not have done a lot, but we did something out of the kindness of our hearts to try to send a positive message.”

Ferguson is familiar territory to Vasser, who graduated from McCluer High School in neighboring Florissant, Mo. He and his wife, Carla, frequent Florissant Road businesses like the Ferguson Brewing Co. and Cork Wine Bar. As of August, he was starting his final semester in UMSL’s MFA in Creative Writing program. In addition to “Picking Up in Ferguson,” Vasser also penned “At Cork” and has found a new focus as an arts activist, creating art in response to trauma.

Vasser, now an instructor at Harris-Stowe State University in St. Louis, wants people to understand that what happened in Ferguson brings up issues of race, status and disparity that are global in nature.

“This isn’t just a Ferguson issue,” he said. “It’s a St. Louis issue; it’s a U.S. issue; it’s a world issue. This is going to take time to rectify. It’s going to take patience, and it’s going to take tolerance.”

–Rachel Webb

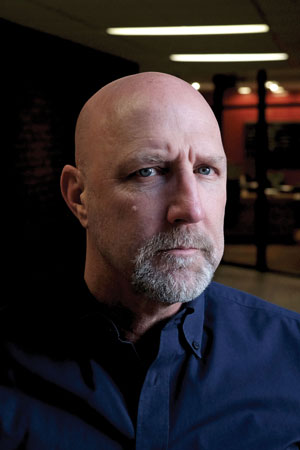

David Klinger, criminologist and media source

David Klinger, professor of criminology and criminal justice at UMSL, has done media interviews for most of his career. As a former Los Angeles and Redmond, Wash., police officer and an expert on use of force, reporters from coast to coast seek his insight numerous times a year. But shortly after the death of Mike Brown, Klinger knew this was not his normal sound bite.

David Klinger, professor of criminology and criminal justice at UMSL, has done media interviews for most of his career. As a former Los Angeles and Redmond, Wash., police officer and an expert on use of force, reporters from coast to coast seek his insight numerous times a year. But shortly after the death of Mike Brown, Klinger knew this was not his normal sound bite.

“I realized this was different when the national press parachuted in, and that was within a pretty short period of time,” Klinger says. “I would get into the office and my voice mailbox would be full, and I’d have a bunch of emails and press inquiries literally from across the globe.”

In the weeks after the August shooting Klinger spent up to 10 hours a day responding to press inquiries.

As he became the face of law enforcement procedures and protocol during the unrest, not everyone agreed with what he had to say. That often included the reporters.

“Occasionally, I would have anchors say things like, ‘Well, Professor Klinger, isn’t it true that…’ and I would have to say, ‘No, you’re absolutely wrong and here’s why,’” Klinger says. “They didn’t exactly know what to do with that, but they didn’t run the other way or shut me down.”

Klinger is unsure what the coming year has in store for the healing of the local community.

“It’s become a social movement that is essentially divorced from the reality of the event that has mobilized it,” Klinger says. “So trying to articulate in my own mind how it might play out, I can’t; because I can’t draw links with any sense of logical progression.”

–Jennifer Hatton

Andrea Schmidt, street medic

After Aug. 9, Andrea Schmidt knew one thing for certain – she wanted to help. For the then-senior nursing major at UMSL, that took the form of street medicine.

After Aug. 9, Andrea Schmidt knew one thing for certain – she wanted to help. For the then-senior nursing major at UMSL, that took the form of street medicine.

“Feeling like I had a role and that I could put my skills to use was important,” Schmidt says in an interview on the six-month anniversary of Michael Brown’s death.

In the middle of protests she worked in a team of medics as she flushed more than 50 people’s eyes with “LAW,” a mix of liquid antacid and water that helps neutralize acid from tear gas and pepper spray. The medics always work in pairs while marked with red-duct tape crosses and are considered neutral.

“Things were scary,” she says. “I mean there were police officers with automatic weapons pointed at us, and I had never even seen an automatic weapon at that point. It was very terrifying. I had never seen armored vehicles line up on a street like that before. It was a war zone.”

In the fall, she helped to officially form Gateway Region Action Medics, a small collective based off the Medical Committee for Human Rights from the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s. GRAM now hosts trainings for the public.

“Our goal is to ultimately put that education and that power in the people’s hands because they’re the ones that can use it every day,” Schmidt says. “And it’s not just in a protest; it’s in the community.”

–Marisol Ramirez

Brian Hutchison and Holly Wagner, counselors

Brian Hutchison and Holly Wagner, assistant professors of counseling and family therapy in the College of Education at UMSL, were called on to help in the aftermath of Michael Brown’s shooting death as emotions ran high and questions were left unanswered.

Brian Hutchison and Holly Wagner, assistant professors of counseling and family therapy in the College of Education at UMSL, were called on to help in the aftermath of Michael Brown’s shooting death as emotions ran high and questions were left unanswered.

The Ferguson-Florissant School District asked Hutchison to help prepare teachers to respond to students’ questions and process their own feelings. Hutchison took a team to the school district, and was also asked to help others in the community express their feelings.

That’s when he pulled in Wagner. She has experience helping individuals use sand trays and story stones to express their feelings and heal from traumatic events.

“Facilitating these narratives through the use of sand tray work and story stones provided the healing space that so many desperately needed at that time,” Wagner says.

Hutchison says they will continue to help.

“The process of transitioning to healing and action will be gradual,” Hutchison says. “So, we are in it for the long run.”

His hope for healing is open communication.

“Cross-perspective dialogue is the most important thing to me,” he says. “Different sides of the political issues, the communities involved, the color line, need to learn to develop empathy for others’ views and listen with empathy so that all are heard.”

–Jennifer Hatton

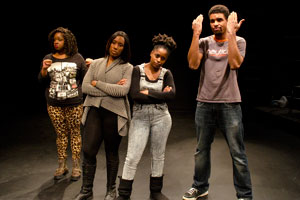

Felia Davenport, Jacqueline Thompson and Kenyata Tatum, actors

A snowy weekend at the end of February seemed far removed from the heat of August, but a workshop organized by UMSL faculty sought to channel the community’s feelings into positive action.

A snowy weekend at the end of February seemed far removed from the heat of August, but a workshop organized by UMSL faculty sought to channel the community’s feelings into positive action.

Theatre of the Oppressed is a New York-based organization that helps communities deal with issues of conflict and racism through non-violent means. Representatives from TONYC visited Ferguson shortly after the death of Mike Brown, but UMSL theater faculty saw an opportunity for more involvement.

“Whether it be something like Ferguson, or discrimination in general, religion, or politics, this is about how to find a cathartic way to release everything and say your piece without violence,” says Felia Davenport, associate professor of theater.

Jacqueline Thompson, assistant professor of theater, worked with the Shakespeare Festival St. Louis to bring instructors to St. Louis for intensive training. Participants included students, teachers and other community members who presented short plays to an audience at the end of the workshop.

“A lot of our students deal with difficult situations every day,” Thompson says. “These are the tools that will let them create their own work to create social change in their communities and throughout the world.”

The work brought up raw, intense feelings among the participants, said UMSL theater major Kenyata Tatum. The workshop inspired Tatum to consider using acting as a form of activism, she said.

“A lot of people were getting heated in the conversations we were having as a group, but eventually we made it to the point of making the play and putting our differences aside,” Tatum says.

–Rachel Webb

This story originally appeared in the spring 2015 issue of UMSL Magazine.