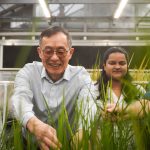

Paige Vaughn, a doctoral student in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, studied ways police work to build trust with residents and reduce crime while working as an intern in the East St. Louis Police Department. (Photo by August Jennewein)

Paige Vaughn wasn’t having any trouble keeping busy last spring while managing a full schedule as a doctoral student in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

She was finishing up her required coursework and beginning to look ahead to her qualifying papers while also serving as a graduate research assistant on projects with Assistant Professor Michael Campbell and Founders Professor Richard Rosenfeld.

But Vaughn just couldn’t seem to stay away from to the Police Department in East St. Louis, Illinois.

“She was there sometimes every day,” East St. Louis Police Sgt. Lester Anderson said. “She saw the whole ins and outs of what goes on.”

It was Anderson who helped her land what was supposed to be a 10-hour-a-week internship with the department.

The two first met in the fall of 2016. At the time Vaughn was in her second year of the PhD program and enrolled in a qualitative research methods course. She had developed a particular interest in crime clearance, and she wanted to learn more about the challenges police have solving cases and seeing that perpetrators face prosecution.

“We don’t really know what can lower or increase violence,” Vaughn said recently. “We think that increasing crime clearance might help promote police legitimacy and lower something called legal cynicism [among the public], but we’re not totally sure.”

Rosenfeld said crime clearance has in some ways been de-emphasized in an era where hotspot policing – the idea to use real-time crime data, figure out where crime is heavily concentrated and deploy resources pro-actively to those areas – has become a popular approach to crime prevention.

“Paige was taken by this argument, and since then she’s been – I think it’s not too strong a word – obsessed with how research can be done that shows the significance of both pro-active activity and what’s called reactive activity,” Rosenfeld said. “That is, reacting to crimes that have occurred through thorough investigation, apprehension of suspects and so on.”

Vaughn interviewed several police officers from different departments across the metropolitan area and was particularly intrigued to hear about Anderson’s experience working in a disadvantaged, high-crime and predominantly African American community such as East St. Louis.

He offered her insight into why crime rates in the city of 27,000 are so high and the difficulty with closing cases. He also told her about a homicide task force comprised of local, state and federal law enforcement officers – called the Street Level Investigation and Crime Enforcement Team or S.L.I.C.E. – aimed at putting a dent in the violence.

Vaughn wanted to see for herself so ended the conversation by asking if she could go to East St. Louis and join him on a ride-along through the community.

She wasn’t fully prepared for some of the scenes she saw. Signs of disadvantage and poverty are hard to miss in East St. Louis, where it’s not unusual to notice bullet holes in the facades of some buildings or stray dogs roaming the neighborhoods.

But Vaughn was fascinated to see the way Anderson interacted with residents – with the respect he showed them reciprocated by people they encountered on the streets.

“He, like a lot of the officers, grew up there, and it was just so cool to see how he had this vested interest in the community,” Vaughn said.

Vaughn wanted to observe more, so she inquired about the possibility of working an internship with the department and won the approval of then-Chief Michael Hubbard.

“That kind of initiative is very, very rare in students,” Rosenfeld said.

The opportunity to get an up-close look at a part of the criminal justice system fell in line with other experiences Vaughn had dating to her time as an undergraduate at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

She had volunteered with the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Victim-Witness Assistance Program and also with The Francisco Homes, an organization with a mission to support formerly incarcerated individuals trying to re-integrate into the community.

In between graduation and enrolling in the PhD program at UMSL, she spent a year with the Jesuit Volunteer Corps, working for the South Alabama Volunteer Lawyers Program, which provides pro bono public legal services to low-income citizens in and around Mobile, Alabama.

As an intern in East St. Louis, Vaughn researched available grants and wrote applications in hopes of securing needed funding.

“In our predicament, where we were, it was amazing because it took so much off of us,” Anderson said. “We were already short-staffed. We’re 56 men under what we should be as far as manpower goes, so all the little things that we didn’t have to deal with, it just made it a lot easier for us.”

Vaughn learned to navigate the state bureaucracy to secure a donation from the Illinois State Police for some bullet-proof vests for auxiliary and volunteer officers. She also made attempts to win support for bigger items such as patrol cars and a new dispatch system, but those efforts proved more challenging.

When she wasn’t working on grants, Vaughn helped make improvements to the department’s website and build its social media presence.

There were also opportunities for her to go on additional ride-alongs and converse with Hubbard, Anderson and other officers. What she observed helped inform her thinking about methods of combating crime.

“It’s tough because you don’t want to become biased,” Vaughn said when asked to explain the value of that on-the-ground experience for her research. “But if you don’t see the places that you’re researching, it’s hard to have a realistic view of them.”

It could also prove important should Vaughn decide to pursue work shaping policy after completing her PhD, though she remains undecided on her future career path.

She is currently working on her qualifying papers and facing a deadline in September. One is empirical on crime clearance in African American communities. The other is theoretical on police response and prevention.

Rosenfeld would like to see her continue to explore those topics more deeply.

“I’ve been pushing her to bring together this work she’s done in reviewing the literature and her own research on the importance of combining both pro-active and reactive strategies,” he said, “both to reduce crime but also to inspire confidence among people in very, very dangerous neighborhoods, economically disadvantaged neighborhoods.”