Biochemistry and biotechnology major Sharla Friend got to combine her dual passions for sailing and science last spring as she took part in the SEA Semester Marine Biodiversity and Conservation Program. (Photo by August Jennewein)

Sharla Friend has had a couple months now to readjust to life on land.

She’s fallen back into the routine of taking courses as she works toward a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and biotechnology at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, and she’s on track to graduate next fall.

But there’s a part of her still longing to be out on the ocean, rising before dawn to gaze with wonder at the stars blanketing the sky or deploying scientific equipment to help in her search for secrets below the surface.

Friend was one of 12 university students around the country who took part in the Sea Education Association’s SEA Semester Marine Biodiversity and Conservation Program last spring. They spent almost six weeks aboard the tall ship “Corwith Cramer” and sailed from Key West, Florida, to Bermuda and then to New York, conducting field research throughout their voyage.

To call the experience life-changing would be underselling it, not just because of the scientific training and sailing lessons she received but also because of the feelings she had being out on the water.

“If anybody has the chance to just go out to a point in the ocean where they can no longer see land, do it,” Friend said. “Do it once in your life. It is 100 percent worth it. You have this surreal feeling of how small you are and it changes you.”

A master’s class in sailing and research

SEA was founded – by Corwith Cramer Jr. and others – in 1971 with the aim to provide undergraduate students the opportunity to study the ocean from a variety of academic perspectives, all from the platform of a traditional sailing ship.

It is affiliated with Boston University and headquartered in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, as a part of a renowned community centered on oceanographic teaching and research near the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

That’s where Friend’s experience began last February after making the drive across the Midwest and upstate New York, then on through to the eastern edge of Massachusetts, where she laid eyes on the ocean for only the third time.

Sharla Friend joined 11 other university students from around the country aboard the “Corwith Cramer” last spring. (Photo courtesy of Sharla Friend)

Once there, Friend met her fellow students – all enrolled full-time at different universities, most located along the Eastern Seaboard but also as far away as Washington state. They moved in together in a house near WHOI and began getting crash courses in oceanography, conservation in the marine sciences and the politics associated with it, and also nautical science, which combined a look at climate, weather, physics and sail handling.

The first month on campus flew by, and Friend suddenly found herself on a plane toward Key West, where the adventure kicked into high gear.

“Corwith Cramer” left Key West on March 28 with a load of 30 passengers – including the students, engineer, deckhands, steward and a small group of voyagers. It took them almost four weeks to sail to Bermuda.

The students were split into four groups and assigned different research projects. Friend’s group examined the microbial community living in the twilight zone, the part of ocean that’s anywhere from 200 to 1,000 meters deep and just beyond the reach of sunlight. They learned field techniques for obtaining the deep-sea microbes and then lab techniques for DNA extraction, sequencing and molecular analysis.

Another team worked on building a database of animal life found living in the sargassum – the sea grass found floating freely in that part of the ocean – while still another spent time studying the sargassum itself. The last team zoomed in to investigate a parasite living on a particular species of shrimp. Each team was not only in charge of the details of their own research projects but also responsible for assisting with data collection for each other’s projects, “Many hands make light work of large projects.” said Friend.

But their jobs were not limited to the lab.

“I presumed as students we would be doing the science and just taking classes,” Friend said. “But every person on that ship was a working hand.”

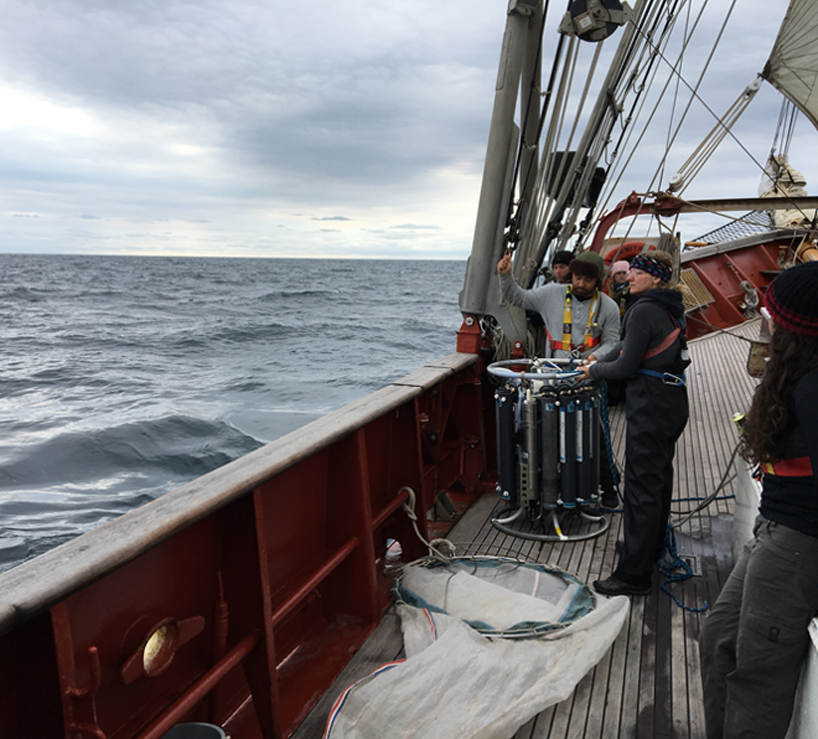

Sharla Friend prepares the hydrocast for deployment from the deck of the “Corwith Cramer.” (Photo courtesy of Sharla Friend)

Each day got broken up into six-hour shifts, and they took turns filling various roles on or below the deck. They received lessons on spotting, navigation, weather prediction and how to handle the lines to control the sails.

Friend had some background in sailing, racing a 14-foot Rhodes Bantam dinghy on weekends with her fiancé the past few years with the Creve Coeur Sailing Association. But SEA was a master’s class.

As busy as it all kept her throughout the voyage, she still found time to snap thousands of photos and record countless more GoPro footage and also stopped to appreciate moments of overwhelming calm and beauty.

“For me, it was very emotional,” Friend said. “There were moments where I would just be standing there and then looking out at the vast water and next thing I’m crying because the sunset is so beautiful or the weather’s perfect or I just saw something like a tiny squid that I held in my own hand but I’ve never seen before.

“There’s so much we don’t know and don’t understand about the ocean, so it makes it very alluring.”

A door into science

Friend never imagined having that type of experience growing up in southwest Missouri. There was no reason to with the closest shoreline some 700 miles away.

She did grow up with a keen interest in science and took to reading books about viruses, including Ebola, in her free time.

Friend was not a standout student, however, and she didn’t go straight to college after graduating. Instead she found a series of jobs in retail and worked for a time as an optician. She was 24 when she finally decided to continue her education.

By then, Friend had moved to St. Louis, and she attended a seminar on bees at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center.

Afterward, she found herself mingling with a woman who told her about St. Louis Community College’s biotechnology program, located in the Center for Plant and Life Sciences on the Danforth campus.

Sharla Friend holds samples of free-flowing velella velella found near the surface of the ocean. (Photo courtesy of Sharla Friend)

Friend, tiring of retail, had been looking for a way into a job in the sciences. She wound up taking a tour with the program’s director and liked everything she heard and saw, so she enrolled.

“I was like, OK, two years, that’s nothing, and I’ll immediately be working in the labs,” Friend said. “I was just sold, so I did it, and I’m very glad I did.”

The experience opened doors, including to an internship in the transformation laboratory at Benson Hill Biosystems, a crop improvement company that’s trying to enhance photosynthesis and various plant products.

In her final semester at St. Louis Community College, she was accepted into the NASA Community College Aerospace Scholars program and got to spend time at the John C. Stennis Space Center in Mississippi.

That experience proved particularly memorable because of a lunch she had with a team of NASA oceanographers toward the end of her stay.

“I got to sit with them, and we just chatted,” she said. “They told me about how they go out on boats into the ocean, do field research for a couple of months at a time and then come back and analyze all the data. They blew my mind. I didn’t even know that that realm of science existed.”

Called to the sea

With her associate degree in hand, Friend hit the job market and landed a position as an analytical chemist tech for Alkem Laboratories, a pharmaceutical company in Fulton.

Friend spent a year there and enjoyed the work more than she ever expected despite its heavier emphasis on chemistry and not biology, her first passion. But she quickly concluded she needed more schooling.

Sharla Friend spends time on the weekends sailing with the Creve Coeur Sailing Association. (Photo by August Jennewein)

“There’s a huge glass ceiling in the sciences,” she said. “I could be a tech forever, or I needed to go to school and not be a tech anymore, which is unfortunate.

“In IT, you don’t experience those glass ceilings. You can just keep climbing. But in the sciences, you can move lots of lateral ways but not up unless you have those letters. So, here I am, I’m going to try and get those letters.”

The affordable tuition and ease with which she could transfer her junior college credits made UMSL an easy choice.

Friend counts herself fortunate to have started when she did last fall, right as the university completed renovations in Benton Hall. She’s enjoyed taking courses there and throughout the science complex, and she’s learned to take full advantage of campus tutoring labs.

But Friend also kept remembering the conversation she had with those oceanographers and knew she wanted to do more. That prompted her last fall to google opportunities for scientific study at sea, which is how she found the SEA Semester program.

Friend ultimately received a $25,000 scholarship from SEA’s generous donors, and it covered all but $5,000 of the program’s tuition. She worked with Nate Daugherty, the study abroad and international exchange coordinator with UMSL Global, to ensure as much as the coursework as possible that she did through the program would transfer.

Eyeing a return to the water

Friend’s semester on the “Corwith Cramer” crystalized the direction she wants to take her career. She aims to do marine genetic research and has three more semesters before she can start full-time in the field.

Friend believes she’ll be well prepared.

“The biochemistry is definitely giving me a foundation that I didn’t have from just getting a tech degree,” Friend said. “I definitely think that I have a lot of lab and technical skills. UMSL is just filling in all the gaps.”

Having her degree will be invaluable no matter what she does next. But her vision keeps returning to the water.

“I’d like to live on my own sailboat, doing my own genetic field research and somebody funding me, whether I have a crew or not,” Friend said. “That is it. So, if I can get to that dream, that would be great.”